H.264 (also AVC), H.265 (also HEVC) and VP9 are video compression algorithms, i.e. mathematical rules with which it is possible to reduce the memory size of videos. We will only briefly explain the technical background and want to show you what you have to pay attention to in everyday life.

Why are videos compressed?

Why compress videos at all? Because nowadays, most people stream videos: be it from YouTube, a media library or iTunes. All data must somehow pass through the Internet and since not everyone has a fiber optic line, it is of course advantageous if as little data as possible is involved. The output information in best quality is thus reduced, if possible in such a way that you does not notice it in the picture.

This is possible with algorithms that try to summarize the corresponding information in the smartest way. Here you can read the details for H.264, H.265 and VP9. After the transmission has taken place, you have to decompress (or decode) the information to display it correctly. Very simply one could say that instead of the information “77777777” one simply transmits “8×7”, which is much shorter. Once the data packet has arrived, you simply turn the information “eight times the seven” into “7777777” again. For video compression, of course, completely different complexities are used. 🙂

But one thing is clear: the encoding reduces the amount of data considerably, but it has to be decoded again, which also requires a lot of computing power. On mobile devices, this is disadvantageous, because if a lot of computing power is required, then the battery life logically decreases and you don’t want that. So you pour the algorithms you need for decoding into hardware: With the “Quick Sync” function, Intel integrates areas into the processors that are only responsible for decompressing video. Since these are so highly specialized and do not do anything else, they are very efficient and require hardly any energy. Apple does the same in the iPhone and iPads with its own chips.

H.264 AVC was good, H.265 HEVC and VP9 are better – and more complex

H.264 has been the standard over the last few years (and still is for resolutions up to 1080p) when it comes to video encoding. Whether you buy a movie from iTunes or watch a Blu Ray, the movie is encoded in this format. Pretty much any device in the world can handle this standard. But now 4K is coming around the corner and data rates are increasing significantly. So you want to compress it even more in order to somehow limit the increasing amount of information: H.265 was invented. This is about 30% more efficient. So you could make a video that is encoded in H.265 instead of H.264 even smaller.

This further reduction of the amount of data, however, is bought at the price of increasing complexity: both the encoding requires more computation time, as also the decoding. But we don’t have a problem: we can simply put it back into the chip hardware and don’t need more power. And that’s how it’s done: both Intel and Apple can easily decode 4K videos from the iTunes Store in H.265 via hardware.

Now a third codec comes into play: Google (and YouTube as well) doesn’t want to use H.265 as successor of H.264, because it has license costs. The developers naturally want to earn money by using H.265. Google, however, does not want to pay and therefore uses the VP9 codec. This codec is open and can be used without license fees. It is, so to speak, a qualitatively similar alternative to H.265. Some say it is a bit inferior, but it plays in the same complexity league as H.265. And we remember: for the decoding hardware support would be great.

Apple only supports H.265, Google only supports VP9

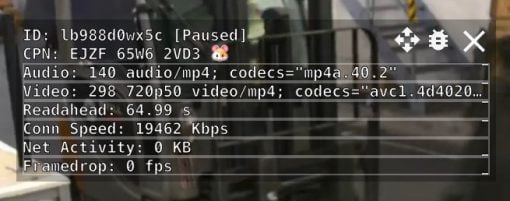

And right now it becomes interesting for Apple users: Apple does not officially support the VP9 codec. They decided for H.265. Google decided against H.265 and for VP9. This now leads to the following situation: With Apple products, YouTube streams can only be viewed up to a maximum resolution of 1080p, as higher resolutions are only offered in VP9. In addition, the bit rate is optimized for VP9 encoding at lower resolutions. This is sufficient for the new better codec, but the videos also offered in H.264 look around 30% worse. So YouTube shows that they don’t even want to support H.264 in good quality anymore.

Apple chose H.265 HEVC, Google VP9.

What does that mean for you in real life? If you use the YouTube app on your iPhone, you won’t be able to play videos in a resolution higher than 1080p. Furthermore, only videos in the H.264 codec, which Apple supports, will be offered. But these look much worse than the VP9 versions, which the iPhone can’t handle. The same is true for the Apple TV: 4K YouTube is impossible because YouTube doesn’t offer H.265 and Apple TV doesn’t support VP9.

On the Mac you can simply use another browser than Safari: with Firefox, Chrome or Opera you can play VP9 videos. The decoding is then simply done via the processor. Not very efficient for mobile use. You can try the whole thing at Opera: with battery saving function, YouTube H.264 video is retrieved from YouTube, without VP9. So you can compare nicely.

Hardware acceleration for VP9 is still scarce

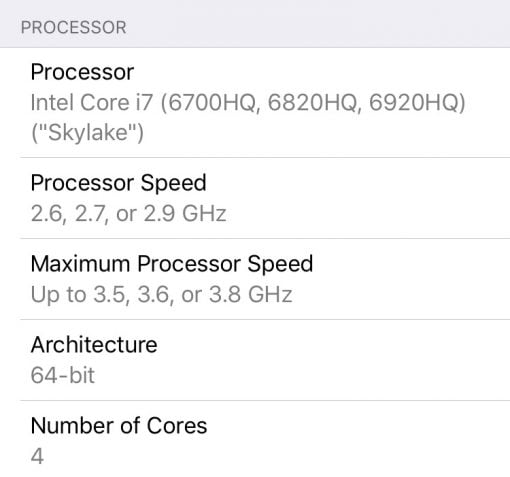

A VP9 decoding in hardware is also available with Intel’s Quick Sync, but your processor must be from the Kaby Lake series, that would be MacBook Pros from 2017 or later. Even the 2016 models can’t decode VP9 in hardware, mobile Apple devices can’t anyway. (And it’s also not quite clear whether macOS offers this, even if the processor is capable of VP9). For comparison: H.264 even computers can go back six generations, H.265 at least the three older ones. With this tool you can check which generation is in your Mac.

This also reveals a second problem: Google blocks especially older hardware with good video quality or overtaxes it with the VP9 codec. Even on old computers, for example, the more complex and computing power consuming VP9 is delivered in Chrome and Firefox, even if it is only about smaller resolutions up to 1080p. But there is at least a plugin for desktop browsers to force YouTube to deliver the older codec and use the hardware acceleration – Safari only gets H.264 anyway. It’s clear that YouTube doesn’t have to deliver everything in 4K and older codecs. But at least decent 1080p or 1440p in H.264 should be possible.

Currently YouTube seems to test out how far you can turn the quality screw downwards. You can read here how much the qualities differ and what you can do alternatively.